Panel Discussion Tackles Designing for Diversity /

(this is an article I wrote for UrbanToronto) The term ‘diversity’ in its cultural sense is frequently referred to in Toronto but it encompasses a much broader range with respect to language, gender and age, including people with disabilities and special needs. The Inclusive Design Institute (IDI) at OCAD University, Canada’s first research hub focused on digital inclusion, designs information and communication systems to work with all potential users. It hosted a panel discussion entitled Traverse – Stories from the Built Environment that brought together speakers in multidisciplinary fields to share their perspectives and present examples of accessibility in such areas as: architectural design, transportation, environmental policy, legislation, and computer technology.

Vancouver's recent ban on doorknobs in new construction in favour of easier-to-manoeuvre lever handles is a progressive move in the broader discussion of inclusion. Removing barriers in our built environment doesn’t just help those with disabilities but improves the standard of living for all. Curb cuts are a frequent analogy of ‘universally accessible’ design. Not only for those in wheelchairs, they are better for the elderly, for people with strollers, or those bearing groceries. The IDI makes a distinction between Universal and Inclusive Design: the former has its origins in architecture and industrial design and is linked to a fairly constrained categorization of disabilities. Inclusive design, on the other hand, takes everyone into account. It recognizes commonly ignored non-visible disabilities, such as cognitive impairment or environmental illnesses.

Accessibility has a certain stigma about it. It is oftentimes associated with ‘static’ design but those notions are being challenged. When Quadrangle Architects relocated to a new space, they conceived a fully accessible office that showcases how universal design can be beautiful and creative. Panellist Susan Ruptash, the firm’s Managing Principal, illustrated some of its features: easily adaptable modular furniture systems; generously-sized rooms and corridors; and, a single-use universal toilet room with the silhouette of a person in a mobility device and dots in decreasing size to indicate the reach range (below left). The firm cleverly uses graphics as a way to educate its own staff on clear floor space requirements and colour contrast minimums (below right). “The graphics are a bit esoteric and we like their storytelling aspect – they become an opportunity for conversation,” says Ruptash.

Full-glass panels are demarcated with vision strips (below right) that integrate profiles of building projects and corporate branding which the firm saw as a way to “show our clients how it can enhance the design of space and not be seen as a limitation.” Because people perceive space in a number of different ways, the architects also incorporated theories of wayfinding in the office’s layout using varying colours, materials, and textures.

Quadrangle sees advocating for a more accessible world as one of its key roles. It espouses the philosophy that integrating universal design from the beginning results in a far better outcome than modifying existing space, which is more costly and often results in inferior design.

Panellist Luke Anderson – a paraplegic himself – has experienced more barriers than most. The professional engineer has taken on the challenge to change the environment of ordinary life, and is gradually doing so through the work of StopGap, a non-profit company he co-founded. Its most recent initiative, The Ramp Project, provides retrofit ramps in various sizes and colours to make existing structures – those burdened with a curb – immediately accessible. Because it is not permanent, the ramp is not required to meet the requirements of the Building Code. It is a low-cost, low-tech makeshift solution to a problem and even comes with assemble-it-yourself instructions. Now launched in 12 communities across the country, these ramps are being snapped up by shop owners eager to make their businesses more welcoming to all. And the bright colours definitely draw attention. It is an initiative – not a protest – and as much about raising awareness of the barriers as improving access to individual buildings. Retrofitting later is more costly.

And the barriers extend beyond the built environment. Our physical and digital worlds are increasingly merging. The IDI and its offshoot Inclusive Design Research Centre (IDRC) create products, software, and adaptive technology that support inclusion. They see disability as a “mismatch between the needs of the individual and the user interface." Accessibility, then, is the adaptability of the system to the needs of all.

Despite what we might think, the majority of us are not ‘typical’ or ‘average.’ While Universal Design creates a common design that works for everyone, Inclusive Design seeks to accommodate the needs of each individual and the digital realm gives designers the freedom to do just that. It is a one-size-fits-one approach instead of one-size-fits all. Jutta Treviranus, the institutes’ Director, describes how they are “working on a way to deliver to everyone something that is personalized – what you need, how you need it, when you need it.” She has played a leading role in developing accessibility legislation, standards and specifications internationally. The IDRC designs broadly implemented innovations and technology such as Tecla, a bluetooth box for mobility impaired mobile phone users. To learn about these, and find more open resources promoting accessible information and communication, visit http://idrc.ocad.ca/.

The discussion not only brought exposure to issues of inclusion but it also reinforced how real value comes from the conversations that designers have with each other and the need for ongoing collaboration. Using principles of inclusive design, we can create attractive designs that are AODA compliant and user-friendly, allowing everyone the opportunity to participate.

IN Series is a series of public presentations and events on a wide variety of topics from the engaging and thought provoking field of Inclusion: Accessibility, Health, Education, Art, Culture and Design hosted by the Inclusive Design Institute (IDI), at OCAD University. The IDI is a hub of applied research that addresses the challenge of design that is inclusive of the full range of human diversity with respect to ability, language, culture, gender and age, including users with disabilities, language needs and various cultural preferences.

Brooklyn Community Planning Board Leader Advises Toronto /

(this is an article I wrote for UrbanToronto) Unprecedented building activity in the GTA coupled with the public’s frustration in engaging the development process is creating a shift towards participatory planning practices. Community Planning Boards may be a way to provide a conduit between the community and city government. The Centre for City Ecology (CCE) invited longtime Brooklyn civic leader Craig Hammerman to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the Community Board model and provide insight into what might work in Toronto.

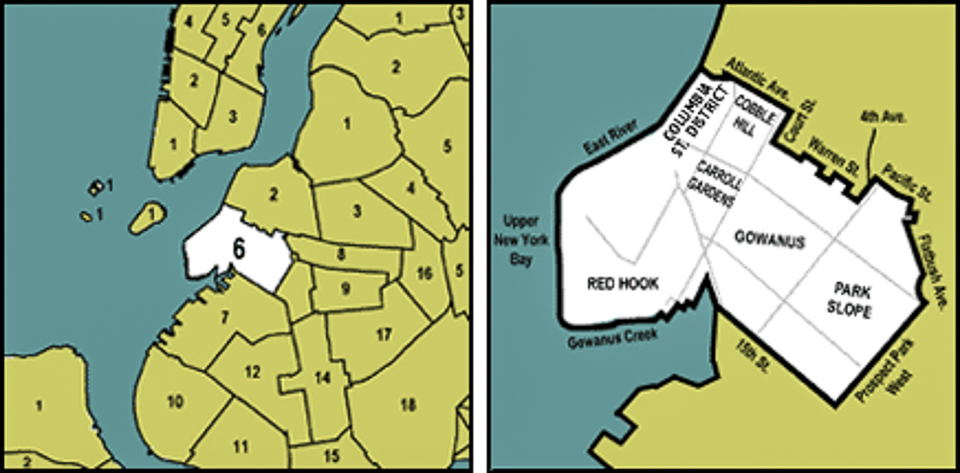

For over 20 years, Craig Hammerman has served as District Manager of Community Board 6 (CB 6), a diverse microcosm of NYC that represents 104,000 residents in a medium density community from Park Slope to Columbia Waterfront. He takes great pride in the work he does: empowering residents and advocating for the betterment of his district. Annabel Vaughan, the CCE’s interim director, summoned Hammerman because of his impressive track record. “He has created such a robust dialogue in that the community has a real say in community issues in the neighbourhood,” Vaughan said.

NYC is divided into 59 Community Districts. Each has its own distinct Community Board (CB), a concept established in 1975 that enables citizens to play an advisory role in their government. CBs are made up of 50 appointed volunteer board members – caring, committed people who represent a diverse range of perspectives and interests. Although getting a group of 50 to make a decision might seem like 'herding cats', parliamentary procedures in place facilitate the process. The CB hires a District Manager as the agency head and operates with a budget of $200,000 with little room for waste.

Aside from being the voice of their community, CBs monitor the delivery of city services, review land use, and are involved in budget formation. They are extremely effective at identifying capital needs in their districts because members live there and deal with the problems every day. All matters are sorted out in various topical committees (e.g. economic development, transportation, education) that meet monthly and report to the full board.

It is interesting to note how CBs intersect with the government. They are required to review and comment on applications to the Department of City Planning; however, as Hammerman emphasizes, “We are advisors – we make recommendations. We are not in a position to implement anything. We need to be as savvy as we can about influencing the decision-makers – that is really what it comes down to.”

Some boards are more effective at negotiating and at handling challenges than others. Fortunately, there is a collegiality among them and a sharing of best practices. In order to deal with each large-scale development proposal, CB 6 devised a Responsible Development Policy that is given to the applicant with instructions to address neighbourhood priorities (i.e. environmental standards) before it presents its case at the hearing. “The more we can anticipate, the more we can build into the process,” says Hammerman. Although they try to be proactive in the planning of their neighbourhoods, CBs are often too busy being reactive to the number of applications flooding in. (There are no planners on staff.)

Hammerman is focused on improving the workings of the board by reviewing: composition criteria; recruitment; public awareness and interaction; communication infrastructure; participatory-discretionary budget; funding model; and, a connection to executive branch of city government. More than other districts, CB 6 is taking a creative approach to engage the public by relying increasingly on social media and crowdsourcing, and making available archived webcasts of its meetings.

Something in the process is clearly working. CB 6 saw 2,000 attend a recent community meeting, which shows that as people begin to feel heard, the turnout numbers reflect it.

There is a recognized disparity across Toronto communities in having their concerns heard at the civic level and being effective in creating change. In some districts, well-organized Resident Associations (e.g. Active 18) proactively weigh in while in others, it is difficult to get input from the local community due to both a lack of expertise and, quite simply, a lack of resident attendance and participation.

Hammerman addressed the group at Urbanspace Gallery, taking questions from an audience that included residents, planners, community activists and legislators. When asked for advice for how we in Toronto can play a more active role in our city’s governance, Hammerman said “Look at how the model of government grew up, where powers are, how decisions are being made, who the players are, and that will give a roadmap to steer where you want to take it.”

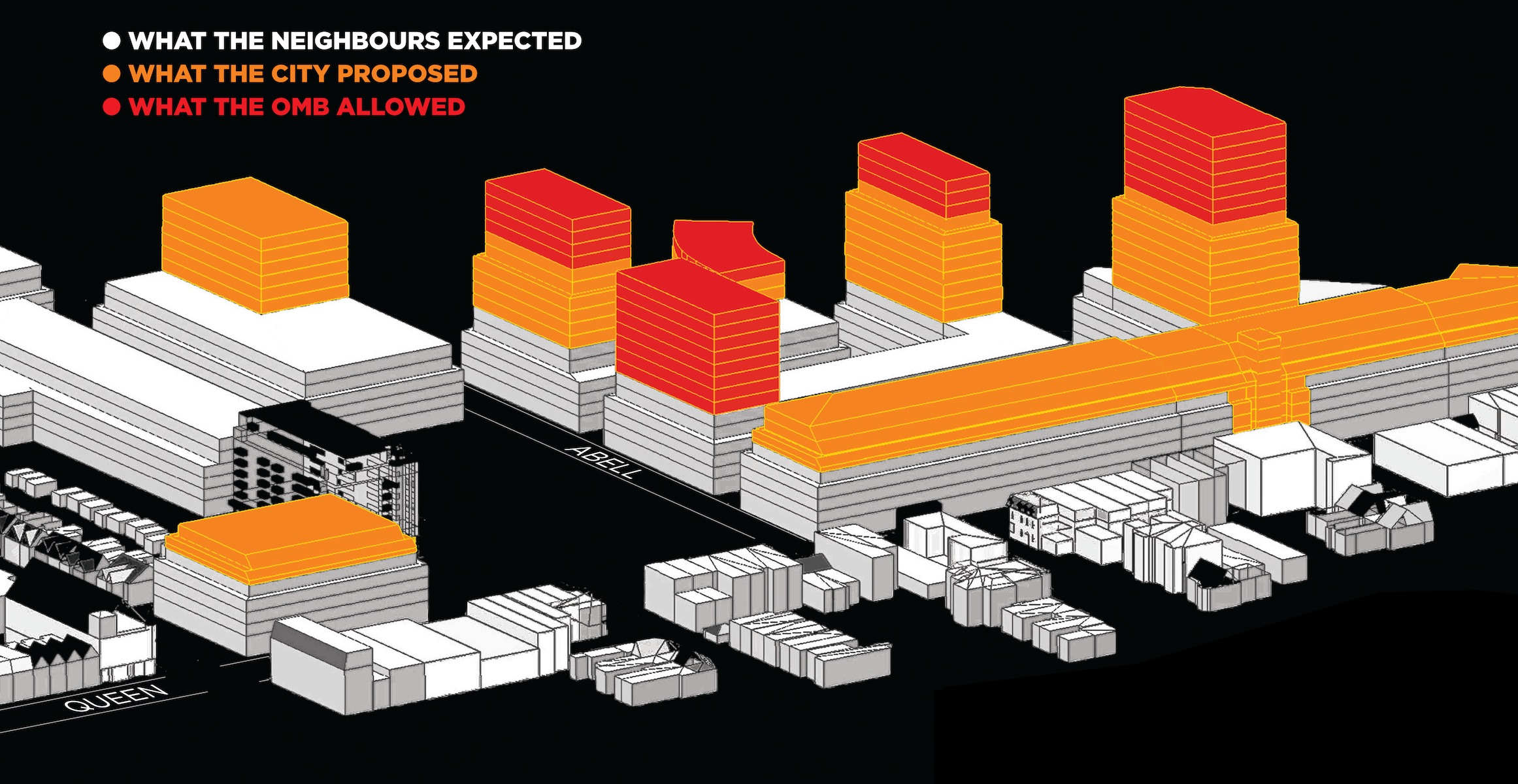

While there are clear benefits in the nonpartisan Community Board approach, practical considerations aside, it is not obvious how to apply it to what we have in Toronto: a planning system that is largely top-down oriented. NYC has distinct but connected planning entities. Toronto struggles with civil servants who lack influence and the contentious Ontario Municipal Board, which can reverse decisions made by City Council.

While the NYC model is one example, Toronto can draw from jurisdictions around the world. “Having a mechanism that is more transparent and consistent could make the planning process a more positive city building process for everyone involved,” says Vaughan.

In May of this year, Councillor Paul Ainslie [Ward 43] successfully passed a motion to launch a pilot community planning board in the suburban neighbourhood of Scarborough (Kingston-Galloway/Orton Park), an area on the verge of being hit with a wave of new development. The intent is to broaden the impact of participatory planning practices that are already at work in some communities across the city. For more information on The Centre for City Ecology and the pilot project, see cityecology.net. Currently on view at the Urbanspace Gallery is the exhibit UNDER THE TENT Envisioning Neighbourhoods.

60 Atlantic: Converting Liberty Village heritage building for today – Part II: Interiors /

(this is an interview I did and an article I wrote for UrbanToronto) The adaptive reuse of 60 Atlantic Avenue by developer Hullmark will create 27,500sf of office space and 12,500sf of retail and restaurant space in a former factory in the heart of Toronto’s Liberty Village. In this 2nd part of a 2-part article, UrbanToronto’s Stephanie Calvet sat down with designer Caroline Robbie of Quadrangle Architects to discuss the interiors fit-out. Anchor tenant INVIVO Communications, an innovative company working at the intersection of science, biology and technology, will move into the top floor early next spring.

PART II: Q&A with Interior Designer Caroline Robbie:

Both the neighbourhood and this building itself have a history as a creative community. Are you collaborating with local artists and artisans in this project and if so, how?

We try to bring an element of custom art into every project we do, whether it is internally generated through custom graphics or through collaborations with artists and industrial designers. The building’s history is being celebrated through a custom version of a Goads Fire Atlas illustration that will be used to film a glazed corridor. The original image was enhanced by our design team to highlight the building. While it is still in the design stage, artist Zac Ridgely is developing a custom feature light fixture for the INVIVO space.

I understand that Quadrangle uses part of its office space as a ‘testing lab’ for design services that it offers, such as investigations in graphics for frit patterns on glass. Have you done similar explorations that have benefitted this project?

We ‘mock-up’ new ways of manipulating images and materials in our studio on a regular basis. This helps not only determine construction methods but it lets us live with something for awhile and gain insights and opinions from the larger studio group. The Goads Fire Atlas film developed for the corridor has been mocked up for some time in a prominent circulation space in the studio.

In a previous interview you said, “buildings need to learn, grow, and change over their lifetime – it’s about adaptability and flexibility.” Does this building have good bones? Is it an example of what you call “durable architecture”?

The one constant in life is change so something as permanent as a building needs to be inherently adaptable. This building and Liberty Village are great examples of the reuse potential of Toronto’s industrial past. 60 Atlantic’s durability lies in its building quality as well as an ability to accommodate changing needs over its lifetime. The beauty of the interior space once extraneous elements were removed was remarkable. We have tried to touch it gently so that the bones are visible.

The following questions are specific to the interiors fit-out for INVIVO Communications, an interactive agency that provides innovative digital solutions – games and apps – to the global pharmaceutical and medical device industries.

The entire office’s lighting design strategy with, for instance, splayed linear tube lighting, is intriguing. What is the guiding concept behind it and what sort of imagery have you incorporated into the workspaces?

INVIVO has healthcare at the core of its purpose, but their culture is about innovation, animation and app development. The environment is definitely not clinical and we needed to respect their playful nature while providing an effective workplace that spoke to the nature of their business. The central design organizing principle is about white matter, the lesser known component of the central nervous system that consists of glial cells and myelinated axons that transmit signals from one region of the cerebrum to another and to other brain centres. White matter is a fine meshwork-like structure that we have referenced in the free-form lighting throughout the main circulation spine of the space.

As you juxtapose the old with new, the basic with the high-tech, what are the qualities that the interiors will evoke?

We hope that the most characteristic quality is of comfort. The mix of materiality and technology, linked through the energetic culture of INVIVO, will allow the space to embody the modern workplace.

Working in a sector where technology is constantly changing, a company like this one likes to stay on the cutting edge. How will that be reflected in the interiors? Which trends play a part in the design?

We tend not to follow trends but instead make sure we are paying attention to the influences on the businesses of our clients. Technology is such a key component of the business – it has played a big role in the planning. The IT department has been pulled out of a backroom and into the fulcrum of the studio. In our experience, technologies move too fast for us to think we can design to anticipate what will be needed so we defend open, unprogrammed space as it will allow the flexibility that will inevitably be needed.

Toronto is the North American base for medical illustration and INVIVO is one of the fastest-growing companies in the field. Just as there is a need for flexibility to update the ‘feel’ of the brand as it evolves, what sort of flexibility is there in the design of the physical space? Are there provisions for expansion?

There is growth potential on the floor within open office clusters and the overall space planning has incorporated enough balance between spaces for focus and spaces for collaboration that project flow is not inhibited by the design of the space.

Are there any specific technical (communication, wiring etc.) requirements that are appropriate for a company at the forefront that is constantly revolutionizing user experiences and that has a futuristic component?

There are no extraordinary technical components in the design other than to provide a very flexible power and data delivery system throughout the space.

Blue and green were integral colours to INVIVO since its beginnings and have always been part of the branding. Did you utilize the colours in the interior design of the office and if so, where?

No, we haven’t incorporated the branding colours as we are leaving the design of the space intentionally white as a background palette for the artwork that is created by the artists and developers at INVIVO.

Corporate giants like Google, with their unconventional workplaces, have embraced the idea that creative work environments help stimulate minds and inspire innovation. If you subscribe to the notion of a studio culture that allows the space to offer all varieties of collaboration, how do you go about making it happen?

Rather than try to force behaviours, it is better to allow people to hack space. We worked to ensure that the space has good light, great views, is comfortable and has the resources they need like wifi and power, in the right places. Once those elements are in place, companies dependent on innovation provide the right tools, which in turn allow their people to foster creative thought.

For efficiency, the base building design team (architectural, engineering and construction) is coordinating M&E systems with INVIVO directly for their use. How have you proceeded with the rest of the spaces considering the additional tenants have yet to be determined?

We have tried to ensure that base building systems like vertical shafts and electrical feeds are in unobtrusive positions while still providing coverage for flexible multi-tenant floor layouts.

60 Atlantic: Converting Liberty Village heritage building for today - Part I: Exteriors /

(this is an interview I did and article I wrote for UrbanToronto) 60 Atlantic Avenue is a two-storey former industrial building in the west half of Toronto's Liberty Village neighbourhood. Developer Hullmark bought the listed heritage property a couple of years ago and is transforming the outmoded building for today's needs, creating office, retail and restaurant space. UrbanToronto’s Stephanie Calvet sat down with key players Richard Witt and Caroline Robbie of Quadrangle Architects to discuss the 1898 building’s reinvention from both the exterior (Part I) and interior (Part II) perspectives.

PART I: Q&A with Architect Richard Witt

The property at 60 Atlantic Avenue is part of a collection of surviving institutional and industrial buildings that give the area its character. What opportunities did restoration of the structure (not strict preservation) vs tearing down and building anew, afford you?

Keeping the building sets up a very different development and value proposition for the site. If it was a new building, it would certainly have been taller, denser and likely not have the same public space that fits neatly into the ‘L’ of the existing building. The existing building’s internal character has a lot of value once stripped out and it is great to see that being restored.

The building does not display a high degree of craftsmanship but it was determined to have design value as an industrial building from the turn of the 20th century and is listed on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties. What restrictions were put in place on what you could do here?

Retaining the building is the biggest restriction. The conventional economic wisdom would be to tear it down and put something much larger in its place. For many developers the requirement to retain it would not have been very desirable. Luckily Hullmark sees the value in that character – economically as well as culturally, ecologically and urbanistically. There was also the requirement for preparation of a Heritage Impact Statement, prepared by heritage consultant Phil Goldsmith, which outlined a number of considerations, including: the important parts of the building (historical entrance, character of the windows) as well as an analysis of the building’s history, which allowed us to have a discussion about which parts of the building did not need to remain.

Since 1991, Artscape occupied the property as its head office with artists' studios. It infused the neighbourhood with energy and played a catalytic role in the reinvention of Liberty Village from a campus of under-utilized industrial buildings to an important cluster of creative sector employment. In which ways do you see this former winery, newly reinvented as a flagship office, having an alternative effect beyond the boundaries of the actual site?

It is not a single tenant building. So far there is one tenant (InViVo Communications) confirmed for the top floor. As far as I’m aware the upper ground level is still available and there are a number of likely candidates circling for the lower ground level. The occupancy of the building will be much greater than it was previously, which is a big contribution to the neighbourhood energy, and the more than one third of the building will be restaurant or retail uses which connect through to new openings on Liberty and Jefferson streets, as well as occupying a new sunken courtyard [see image below] on Atlantic Ave. There will be a lot of two directional traffic in and out of the building, which will have a big effect on the entire area.

For decades, Hullmark focused primarily on large residential developments around the GTA. Recently it has set its sights on transforming neighbourhoods in popular urban areas of the city. What synergies between the two firms make it possible to partner up successfully?

I’ve always liked the simplicity and clarity of a quote by Hullmark founder Murphy Hull “I had a vision. Over time and with hard work that vision came true.” Hullmark’s vision as city builders aligns with something that Quadrangle have been doing for our entire history: taking buildings of latent value and potential and reinventing them as something new and relevant. In addition to 60 Atlantic we are also doing projects of similar objective at 545 King W and 100 Broadview [below]. Hullmark is still doing large residential developments and, under the direction of Jeff Hull, has been transformed into a more urban-focused developer.

If adaptive reuse can be seen as a financially viable style of historic preservation, why aren’t there more enlightened developers in Toronto ready to reclaim historical sites?

There have always been developers doing adaptive reuse in the city. We’ve been working with them for years on projects like City TV, the Candy Factory, the Toy Factory and many others. Although it may be financially viable, it is more work to achieve the same quantity as with a new build. There are always unknowns and surprises along the way and some of those can be expensive. It requires a lot of commitment and long-term vision from the entire team.

What is the interplay between the limitations of zoning (and its revisions) and the requirements of historical preservation? When does one take precedence over the other?

Zoning decisions have the right of appeal at the Ontario Municipal Board, but Heritage Board decisions do not have that same possibility. In the case of 60 Atlantic there was no Site Plan Approval application necessary though, so there was no potential for conflict.

The transparent circulation spine cleverly reveals rather than conceals the existing building behind it. What obstacles had to be overcome and which conditions fulfilled in order to arrive at the solution?

The addition was a means to deliver more regular leasable space and not have to make costly additions to the building to accommodate things like elevators, new plumbing, and adequate structure for heavy mechanical equipment. It is also a way to create a clear difference in expression from the existing and new work. It was easier to do it that way than the alternative. The only real obstacle was matching up to the existing building which is not very regular, and built in phases at different levels.

The building has small punched windows along its façades that lent themselves well to Artscape’s studios and office spaces (and long prior to that, a winery). Are you incorporating larger glazed sections and/or skylights to accommodate the new program’s open plans, and if so, how?

The building was built in two phases, east and west at slightly different heights. The central north south portion was a through-carriageway. Our first objective in working with existing buildings is to understand what is original and what was subsequently added, which in the case of this building was a lot. There were also lots of elements like loading docks, which had been retrofitted as windows with dodgy brick infill. By taking out all of these pieces we were left with a series of large openings, which could be fitted with glazing and become a new layer of expression that more accurately reflects the original condition.

Does this project epitomize Quadrangle’s philosophy of not just locking a building in time but rather adding layers as the city evolves? (i.e. glass is not verboten under heritage conservation guidelines)

The new glazed elements, new circulation, connections to the street on all sides and new sunken courtyard all engage the surrounding community in a way that the building didn’t before. By renovating and turning a former utilitarian warehouse into a vibrant employment and amenity hub, the building both reflects its history and becomes relevant to the future of Liberty Village. So, Yes.

Adaptive reuse is in and of itself a sustainable approach. Are you pursuing LEED certification for this development?

We are not pursuing LEED certification, although we discussed it in the beginning and were conscious of our responsibilities throughout. We reviewed the requirements and did a lot that goes beyond the code requirements including some significantly more advanced mechanical systems. In the end we didn’t pursue it because of the cost of the LEED process itself.

Liberty Village is undergoing a rapid transformation characterized by thousands of new condominiums set amidst historic industrial buildings. Its east side has become, in the words of architectural critic Christopher Hume, “an over-developed condo enclave,” with little consideration to human scale. What would be your advice for city planners or developers to prevent the same saturation on the west side?

The west side of Liberty Village has the opposite problem to the east. It is almost all designated employment lands with a much lower height limit. I think we are moving beyond the days of single occupancy land-based planning (work somewhere, live somewhere else, shop somewhere else, etc.) and there is a lot of discussion about introducing residential permission to this part of Liberty Village. Permitting residential to a maximum as well as a minimum amount of commercial space would be a good way to build a true mixed-use community and encourage the growth of employment simultaneously.

For 21 years the building was home to Artscape and to 48 affordable artist studio spaces. Not immune to the pressures of the real estate market, the non-profit organization was forced to close this location in 2012. Low cost raw studio space in downtown Toronto is disappearing fast. Can you contemplate ways by which artists and low-profit creative outlets can remain in these neighbourhoods they helped revitalize?

I don’t know if that’s even desirable. I remember that Third Rail art show in Liberty Village when people were living in big warehouses with chemical toilets, and that seems a 100 years ago. Part of being an artist is being ahead of the curve, and once the space around has become popular and mainstream perhaps it is not such a place of creation. Architects have a similar role in residential purchases – a lot of my friends live around Roncesvalles, which was affordable 10 years ago. I don’t think that many architects five years out of university could afford a house there now and where they’re going is probably going to be a great and vibrant area in a few years…

This intervention is simple, sensitive and aware of its context. How do you integrate with the existing fabric of the former industrial precinct while simultaneously anticipating its urban future?

A lot of architectural direction comes from a consideration of broader influences. By looking at the economic patterns of the area, the qualities of the urban context, movement patterns, social activity and a lot more, an obvious design intent reveals itself. Then it is just the business of building articulation. When it comes to making a great city the most important thing is design at an urban level, an understanding of the buildings’ relationship to, and role in, the broader urban fabric. If you have good architects you get beautiful buildings, but that doesn’t make a great city. Ideally you have both, which is what I think we will have at 60 Atlantic.

Stephanie Calvet is an architect and a writer specializing in architecture and design. She can be found at www.stephaniecalvet.com

The Interview: Richard Witt of Toronto's Quadrangle Architects /

(this is an interview I did for UrbanToronto)

UrbanToronto’s Stephanie Calvet sat down with Richard Witt, principal at Quadrangle Architects, to discuss the inspiration for DUKE Condo’s design. The mid-rise building, which takes its name from an amalgam of Dundas and Keele streets in The Junction, is under development by TAS.

How is DUKE different than other recent mid-rise downtown condo projects (King W, Ossington, etc.) in terms of trends and features?

For one, it is a bit bigger than most of the others I’ve done. For example, Cube Lofts has 21 units, Abacus has 42, 838 Broadview Avenue has 40, and Beach Club Lofts has 47 units. DUKE has over 100 units so there is a bit more economy – but the principals are the same. Secondly, DUKE represents a bit of a shift in the market, where mid-rise and avenue intensification is being pursued by a more established developer of historically bigger projects, design-oriented TAS. DUKE also engages with the laneway in an attempt to 'de-service' it to an extent, through the implementation of live/work units (it creates a front door address to the lane and brings in pedestrians rather than just parking and garbage trucks). Lastly, the architectural expression is set up to anticipate a fluid market demand and potential shift: rather than being a composed elevation, it is a direct expression of the unit mix which can be altered through the sales process.

What are the guiding design principles that have facilitated the incorporation of a mid-rise into an existing mixture of low-rise buildings, many of which have a historical character?

Although the buildings around have been there for some time, I wouldn’t characterize the context as heritage rich in terms of its buildings specifically, and heritage is a word that’s overused in this city to mean old. The greater history lies in the neighbourhood and area, in terms of the way it has evolved. Quadrangle has historically been known as a company that works to build communities and responds to contextual clues and this project is no different. There are a number of buildings of different shapes and sizes and this project, through its scale modulation and multiple datum lines, picks up on all of those clues. Additionally, it anticipates the future development to come, so when the one-storey buildings are replaced with future buildings of unknown scale, the response to that future context is also anticipated.

As stated by architect Peter Clewes, “In Toronto, we tend to look at the street as a series of individual buildings, not a streetscape.” Considering this is an infill project, how do you think this building adds to the existing streetscape?

That may be the way he’s working, but we always looks at streetscapes and broader context. We do a lot of master planning work which involves understanding walkability, block sizes, designing for end users, mixture of uses on the street and we also work across a lot of sectors including residential, retail, and office, so we understand how they all come together. DUKE provides street-related retail with good height and proportion, innovative live/work unit response to the laneway, and street-related townhouse-type units that form part of the streetscape. The only side of the building in which we don’t address the street is the party wall to the west where there is no street.

There is an interesting breakdown of unit typologies in the project. Given that the price point for mid-rise tends to be much higher, and given that the units are quite differentiated amongst themselves, who is your main target market?

The target market is anyone who likes the character of the Junction and what that neighbourhood is all about. We have worked with local artists and manufacturers to create a building that reflects those values. The unit mix is extremely varied, to anticipate first-time buyers who want to move to one of Toronto’s coolest areas, people who have owned a house in the area for 40 years and want to live in a condo but stay in the area and everyone in-between.

Did the project require an amendment to an existing zoning by-law? And if yes, how has the project been received by the community?

Yes, it has already received approval for that at Community Council. The community response has been overwhelmingly positive: a lot of supportive comments and encouragement to push the design. I think it is a very enlightened community that deserves a great building. The main concern as with all projects these days is traffic – we have done what we can with this building, but a 100-unit building cannot address the traffic and transit problems Toronto is facing…

Does the project meet TAS’ ‘Four Pillars of Sustainability’ (social, ecological, cultural, economic) and how?

Absolutely. Community engagement and commitment to working with the artisanal nature of local industry has been a primary principal in launching the project. We have used the design, specifically interior and sales centre (designed by local interior designers Mason Studio) as a vehicle to promote their work via the sales centre and inspiration for the interior design of the building itself (also by Quadrangle). The ecological considerations are primarily manifest in the high ratio of wall-to-window in the building (more insulation) but also in many features throughout, such as the planters on the south side which can be used for growing vegetables, the energized parking spaces (see below) and the high level of metering for all services in the individual units.

Does the building follow the apparent trend of providing a low parking-to-unit ratio and what is the ratio for DUKE?

No, the Municipal Authorities are being much more restrictive in their permissions since the introduction of the new by-law last year. The building is providing parking exactly in accordance with the new (and more onerous) by-law. However we have looked for ways to promote sustainable transportation beyond the abundance of available transit, and have made a specific effort to provide energizing to about 25% of the spaces, and well as provision for future energizing of the other spaces, should the need arise.

Has the double-height retail space been designed in such a way to entice lively commercial venues and deter, for example, the usual corner banking outlets that do not enliven the corners of the city?

It has a very high ceiling, and a potential combination or separation of up to three units. It’s not the right proportions for a bank, and not a great corner for it – my hope is a couple of uses, perhaps a gallery/showroom and some kind of café.

What was the inspiration for the common area interior spaces?

The neighbourhood and artisanal industry base.

Was Mason Studio only involved in the showroom design or was it also involved in the interiors of the project itself?

Quadrangle did the architecture and was responsible for the interior design of the building units and common areas. Mason Studio was responsible for the design of the sales centre. However there was a fair bit of cross pollination in the design meetings since the sales centre features much of the interior design for the building, and Mason was in those meetings discussing with us.

How will these transitory functions currently held at the building site, such as free mass outdoor yoga sessions and farmers’ markets, contribute to the project’s acceptance by the community?

Hopefully the nature of those events will move forward with the occupants that inhabit the building. TAS has shown enormous philanthropy in utilizing their site for these kind of events and that seems to have engendered a lot of goodwill towards the project.

So far, what has been the greatest challenge on this project?

The nature and constraints of an urban infill project with so many influencing factors creates a lot of challenges – in the way the building responds to the stable neighbourhood to the south, permits light on to the sidewalk, and stays at a reasonable scale. We face these challenges on every mid-rise project but, though the principals are the same, the response is always different.

Are there any trends in condo building in Toronto that you’d like to see disappear in the near future?

Yes. Lack of imagination, which mostly expresses itself in generic boxes clad entirely in low insulation glazing with “modern design” as the excuse.

Lastly, where do you look for design inspiration?

Nowhere specific, but I'm always on the lookout!

Doha sights and sounds /

I've been fortunate to have the opportunity to spend time in the Middle East. First stop: Doha, Qatar. The next photos are of the Souq Waqif. The labyrinthine market looks deceptively ancient. Although the site dates back 100 years, it has recently been restored to revive the memory of the area. Over the years, the market fell into disrepair and was abandoned as shopping malls grew - and they grew, big-time. Now, the cobbled lanes and whitewashed buildings, made using traditional Qatari architectural elements such as mud rendered walls and exposed timber beams, look to be from a bygone era. Restoration or reconstruction? I'm not sure.

The shopping destination is renowned for selling traditional garments, spices, handicrafts, and animals (alarmingly, lots of dyed pets). Each narrow, covered alley sells a different commodity. I expected to see people haggling over a sale but it was all very civilized, probably because Qatar has the highest per capita income on the planet. There are shisha lounges, galleries, luxurious boutique hotels and Egyptian, Iraqi and Lebanese restaurants. There is also a Falcon Souq nearby (apparently falconry is a big hobby for Qatari men) and a camel pen in the parking lot.

These next shots are of Hey'Ya: Arab Women in Sport, an exhibition celebrating female athletes - amateurs to Olympians - from the Arab world. It featured a series of large portraits of sportswomen from 20 different countries by French celebrity photographer Brigitte Lacombe.

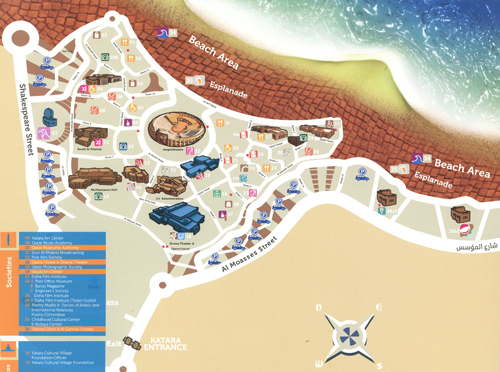

Next up: Katara. It is home to a bunch of institutions including the Doha Film Institute, the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra and the Arab Postal Stamps Museum, connected by a network of lanes shaded with wide-stretched canvas canopies. Katara seeks to promote cultural awareness and acceptance by organizing festivals, exhibitions, seminars, and all forms of artistic expression in this newly created "cultural village" beside the sea...

Open to the sea stands a gargantuan marble amphitheatre, presumably used for concerts and performances. I saw a total of 3 people exploring the vast complex when I visited (not counting a bevy of golf cart drivers). All of this in the blazing Gulf sun ... I couldn’t help wondering who this is actually for.

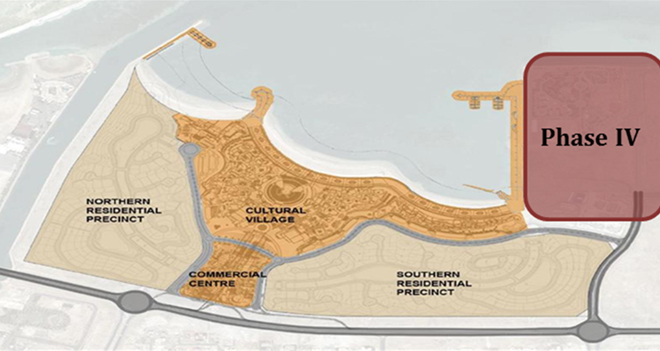

Building has been going strong in Qatar. It has seen the development of new residential areas, new ports and airports, as well as lots of new infrastructure. There is even more envisioned for Katara -- Phase IV will be a mixed-use development as an extension to the Cultural Village.

Mykonos /

Firá (Santorini) /

Firá covers Santorini island’s volcanic edge with layer upon layer of hotels, cave apartments, infinity pools and swish restaurants, all backed by a warren of narrow streets lined with bars and shops. It is a vision of dramatic cliffs and low-lying cubical buildings made of whitewashed local stone.*

The town’s small scale doesn’t deter the cruise ships from all over the Mediterranean and Aegean seas that descend upon the Old Port. Its central location makes it a good base to access many other parts of the island. Fortunately, in the early evening the multitude of passengers return to their vessels and the local restos and cafés taken on a more relaxed atmosphere.

Built on the edge of a 400m high caldera on the crescent-shaped island’s western side, Firá is accessed from sea level by a cable car, donkey ride, or by foot (587 steps) along a meandering rocky path (trafficked by donkeys).

Christoforos Asimis is regarded as one of the island’s most significant artists. For seven years he created luminous religious paintings that fill the interior of Firá’s Cathedral after it was rebuilt following the area's major earthquake of 1956.

The newly established AK Asimis Kolaitou Art Foundation (pictured below) brings together the work of the revered Santorinian artist as well as that of his partner, Eleni Kolaitou (sculpture & jewellery).

Located on the main road from Firá to Pyrgos, the gallery opened its doors early this summer. Designed by son Katonas, who also exhibits his paintings on site, the building features the artists’ residence, studio, and indoor exhibition spaces as well as outdoor venues for music, drama or various performance art events. I had the unique opportunity to interview the family of artists. Here is a video showcasing some of their work.

Christoforos Asimis’ paintings (above) explore the magnificently changing light and landscape of the artist’s home town. It is not difficult to find a lifetime's worth of inspiration here. Island bliss.

*or limewashed with various volcanic ashes used as colours

A day trip around Santorini /

Oia – Santorini’s jewel /

Unfolding along volcanic rocks, the traditional village of Oia extends for almost 2km along the northern edge of the caldera that forms the island of Santorini.

Unfolding along volcanic rocks, the traditional village of Oia extends for almost 2km along the northern edge of the caldera that forms the island of Santorini.

The topographical particularity of this locale is staggering. Santorini’s central part collapsed as the result of a big volcanic eruption in 1660 B.C, forming this imposing cauldron-like feature. Oia can be reached by a road that meanders atop steep cliffs along the eastern periphery of the island. Sections of this road become so perilously narrow and ridge-like that it can barely accommodate two lanes of traffic. Perched 70-100m above sea level, Oia itself is divided by the central road into two sections: one facing the caldera cliff, characterized by white-painted dwellings, once used by seamen, carved into niches in the rock; and the other, a wide swath of largely agricultural land marked by conventional houses.

The ground is composed of successive layers of fragments and lava. The uppermost layer consists of pumice stone and a sub-white ash called ‘theraic earth’ that is easily excavated and gave rise to an underground cave habitation pattern with vault-like spaces receiving light from small openings on the built-out front. Many of the simple seamen's houses have become guest homes, hotels and restaurants, with narrow passageways running between them.

Oia seduces visitors with its blue domed churches, sun-bathed verandas, and quaint cobbled alleys lined with taverns and shops. But most of all, it is renowned for its enchanting sunsets, best experienced at the ruined castle at the tip (above).

A differentiating architectural element in the island’s vernacular is the vaulted roof of dwellings that resulted from their subterranean typology. It became more common after strong earthquakes in 1956 struck the island and destroyed or damaged half of its buildings. Restrictions to new construction have been put into place in order to minimize risk from future earthquakes and to preserve and restore – or find new uses for – traditional settlements.

A number of unfinished construction sites dotting the Aegean landscape stand in watchful reminder of the harsh economic winds affecting Greece.

Montréal /

Redevelopment of Toronto's St. Lawrence Market North in Limbo /

(this is an article I wrote for UrbanToronto) An initiative to redevelop the St. Lawrence Market North site is caught in limbo as the City and the architects work to resolve budget and funding issues in what has already been more than decade-long process. A 2008 competition to replace the aging 1960s north building (a Canadian Centennial project) and to improve the St. Lawrence Market complex resulted in a winning design for which ground is still a long way from being broken.

Next up in the ongoing saga is the consideration by the Government Management Committee and City Council. Toronto's Deputy City Manager, Chief Financial Officer, and Chief Corporate Officer recommend that design work continue, and the necessary budget adjustments be referred to the 2014 Capital Budget Process.

The forecast for the building, based on the Architect's latest design submission, has risen from $74.89 million to $91.46 million. Additional funding of $15.293 million is required in order to advance the project, despite considerable reductions to the Winning Design (below left). It was envisioned as nearly all-glass with exterior wooden louvers, and its five-storey-high central courtyard would bring in plenty of natural light and provide a clear, perfectly framed view north to St. Lawrence Hall. The Architect's revised proposal (below right) accommodates the major program requirements and while significantly less dynamic and permeable in form and spirit, still maintains the essence of the Winning Design.

The original estimate was prepared in 2008/09. The revised project costs are a result of a few significant factors: inflation/escalation; atypical conditions discovered at the site require additional monies for excavation; and, preliminary cost estimates were unsuitably based on a unit cost allocation of a typical structure that doesn't have the level of complexity of this distinct design.

The current St. Lawrence Market North building has been largely underutilized and an initiative to maximize the site's full potential has been ongoing since 2002. In 2008, City Council authorized a design competition to select an architect for the development of the north property. The winning submittal came from Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (the "Design Architect"), in association with local firm Adamson Associates Architects.

The principal benefits that will result from the project's completion include:

- Significant improvement to a city landmark and tourist destination

- Improved compatibility with the heritage character of other buildings in the neighbourhood

- Increased parking capacity (through the construction of 250 new underground spaces)

- Service improvements resulting from the consolidation of Court Services operations into one location

- Creation of new interior spaces that can be used for a variety of community and commercial purposes

The Winning Design included features which have been eliminated or reduced in the current design:

1) Building Height Reduction - height of building has been reduced from 6 floors (including mezzanine) to 5 floors. Space programming efficiencies have been realized by relocating non essential file storage space from the office floors to residual areas of the parking garage. The revised design also eliminates the 4th floor mechanical area by changing the design from a centralized mechanical system to a decentralized system distributed across all floors.

2) Green Roof Reduction – the Winning Design included a separate green roof suspended over the main building roof, excluding the atrium. The revised design includes a green roof as part the building roof.

3) Sustainability Target Reductions – the Winning design stipulated designing to LEED Gold, with the 'goal' of LEED Platinum. The revised design proposes designing to the Toronto Green Standard of Tier 1 (which contributes towards LEED Silver certification).

4) Sun Shade System Reduction - the Winning Design included operable exterior wood louvers, including maintenance catwalks, on the east and west sides of the building. The current design includes a fixed louver system of composite material with an aluminum core and the elimination of the catwalks.

The Architect has informed the City that there are no further design reduction options available other than further reductions to program space, which is unacceptable to the City. As a result, in order for the project to proceed, additional funding is required. The final project cost estimate, based on 100% design, will not be known until the Architect completes the Design Development and Bid Document stages.

Below are exterior and interior renderings of the initial winning design and the adjusted design proposals.

This report will be considered by Government Management Committee on June 17, 2013 and then by City Council on July 16, 2013, subject to the actions of the Government Management Committee.

Athens _ Athína /

Touring Cappadocia /

Cappadocia is the historical name of the region in Central Turkey, 750 km southwest of Istanbul and 300 km south of Ankara. Modern Cappadocia refers to a geographical area with a unique cultural heritage and landscape entirely sculpted by erosion, whose exceptional natural wonders are a popular setting for a variety of activities such as hot air ballooning (see previous post), horseback riding, and guided area tours, some of which are described here. One such outing is a hike in the Ihlara Valley, a picturesque canyon marked by a stream that flows through it and honeycombed with hundreds of rock-cut underground dwellings and cave churches from the Byzantine period. The rock-hewn sanctuaries contain colourful frescoes, some still remarkably intact.

The Underground City of Derinkuyu is an ancient multi-level complex used by early Christians as a hiding place during times of raids, before Christianity became an accepted religion. The vast network of caves sheltered up to 20,000 people and livestock for months at a time. Carved into the soft volcanic rock, its passages extend to a depth of 60m and are connected to other troglodyte villages or subterranean towns through miles of tunnels. Though breathing is difficult, you can descend as far as the 5th level to visit once-occupied spaces, such as chapels, religious classrooms, cellars and stables.

Other memorable spots include Selime, whose dramatic topography (pinnacles) inspired some of the filming of ‘Star Wars’, and Pigeon Valley, named for countless pigeon dwellings carved into the cliffs. (Years ago these creatures served as message carriers, and their droppings were used as fertilizer.)

Panoramic viewpoints of Paşabağı and Devrent Valley reveal mushroom-shaped fairy chimneys and unusual eroded landforms whose volcanic tuff has been sculpted into shapes shapes reminiscent of pillars and spires and even resembling animals – a 'lunar landscape' - like a sculpture zoo made by nature.

The town of Avanos is the center of ceramic art and earthenware production and trade dating back to the Hittites, and here you can see a pottery-making demonstration by kick-wheel technique.

The town of Avanos is the center of ceramic art and earthenware production and trade dating back to the Hittites, and here you can see a pottery-making demonstration by kick-wheel technique.

Sema, the Whirling Dervish Ceremony, is a physically active meditation still practiced by the Dervishes of the Mevlevi order. They aim to reach the source of all perfection by performing a customary dance, of which each of its seven parts symbolizes a stage of the mystic journey called ascension. Cloaked in a white frock and headdress, the Dervishes listen to music, focus on God, and, in a trance-like fashion, spin their body in repetitive circles, revolving as do all other beings and embracing humanity with love.

At the centre of Cappadocia are the towns of Ürgüp and Göreme. Within the region's rock formations, Christian villagers had excavated cells which served as residences, storage, places of worship and refuges dating from the 4th century. It’s a very special experience to stay in a hotel built into existing caves, one that combines dwellings of the Hittite, Roman and Byzantine periods with the comforts of the 21st century.

Göreme National Park and the Rock Sites of Cappadocia have been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. See link here.

Hot Air Ballooning in Cappadocia /

Hot air ballooning in Cappadocia, a historical region in Turkey's Central Anatolia, yields breathtaking views, unrivaled anywhere. Balloons launch just before dawn, dozens at a time. They float silently above surrealistic landscapes dotted with villages, vineyards and fruit orchards. The balloon gently drifts over and between tall, thin rock formations or 'fairy chimneys', through valleys and up over rippled ravines, before touching down in a farmer's field.

Images of Istanbul /

Istanbul - The Call to Prayer /

World Architecture News Awards include Big Wins for TO and Canada /

(This is an article I wrote for UrbanToronto) World Architecture News (WAN) recently announced the winners of the Retail and Leisure Interiors Awards 2012, the most illustrious interior awards around the globe. Whittled down from a bevvy of outstanding international submissions were a number of projects with a Toronto or Canada connection, representing a high percentage of the overall awards. Yay!

Project entries were divided into three distinct categories: Hotels and Service Retailers; Restaurants & Bars; and Retail Outlets (under 200sqm/over 200 sqm). Judges convened in London to select the winners based on the following criteria: "design excellence, originality, quality and mostly, the ability to communicate the historical aspect of a site through its decor.

Taking 1st prize in the category 'Retail outlets over 200sqm' was the transformation of Maple Leaf Gardens, the former home of the Toronto Maple Leafs, into an urban food store and gastronomical mecca for the Loblaws grocery chain. Collaborating with Toronto’s Turner Fleischer Architects, the Aussie firm Landini Associates, who specializes in graphics, strategy and branding, animated the cavernous interior of what was once Toronto's most iconic sporting venue with bright hues of red and orange and larger-than-life typography. The building's history is celebrated through an integrated design approach that incorporates elements from its past: stadium lighting, murals, and a 12m x 12m Maple Leaf sculpture of old stadium chairs. Landini Associates won the big prize and then some, matching the client's initial request of “world's best food store” by creating a hub "Super" "Market" that not only seeks to engage the local community but draws visitors from far and wide.

Other wins didn't come for Toronto locations, but two more Toronto-based firms did very well.

In the category 'Restaurants & Bars', Toronto firm Yabu Pushelberg, known internationally for creating luxurious and refined interiors, won for the grand reopening of the legendary Pump Room restaurant in Chicago. The firm partnered with celebrated New York hotelier Ian Schrager in the re-imaginging of the Ambassador East as chic modern Public Hotel on Chicago's "Gold Coast."

Juxtaposing classic and modern elements, Yabu Pushelberg reinvented the Pump Room, capturing the glamour of the venue's celebrity-filled past and historic club-like atmosphere. The new interiors are striking: a neutral palate dominated by more than 100 hanging celestial resin orbs, bleached-oak tables, and swanky leather chairs. Just as the iconic space was revisited so was the menu, its original classics recreated by world-renowned chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten.

On the shortlist with no lack of accolades is the Joe Fresh New York City Flagship by Toronto interior design firm Burdifilek. The launch of the Canadian retailer into the U.S. market wowed the jury with a showroom that takes over two floors of an historic bank building at the corner of 5th Ave and 43rd St. It's a dazzling sight inside and out, an airy glowing interior showcased through SOM's iconic 1950s glass façade.

In order to protect the historic features of the modernist building—once-dubbed the “Crystal Lantern” by Lewis Mumford—none of the shop fittings were drilled into the floor, walls or ceiling. Instead, the design provides for custom free-floating wardrobes crafted from white, powder-coated metal with sandblasted Lexan panels that can be easily reconfigured by Joe Fresh’s merchandising team into vignettes. The wardrobes seamlessly incorporate monitors, mirrors or backlit billboards to feature clothing and accessories. Joe Fresh bold-coloured urban fashions stand out against the all-white interiors, much like the brand's clean aesthetic.

There is design life in Canada unconnected to Toronto, and an instance of it in Quebec has also landed a major prize.

Hôtel La Ferme by Montreal-based architectural firm Lemaymichaud took home 1st prize in the 'Hotel & Service Retailers' category.

This contemporary take on country hotels in Baie-Saint-Paul impressed the judges with its efforts to preserve the site's colour and authenticity by emphasizing 'craft' and 'local': locally-sourced materials and items, and the showcasing of artisans' work. La Ferme includes barn-inspired wood elements throughout and, fanned out across five pavilions, its 145 rooms and lofts feature various types of rooms with distinct personalities, from railway-themed sleeping quarters with pull-down beds to botanically-themed décor alluding to the site's past vocation in agriculture. The design pairs modern pieces against woven traditions of old, capturing the charm of the Charlevoix region and telling the story of the historic setting.

Architect Craig Webb expands on plans for Mirvish+Gehry Toronto /

(This is an article I wrote for UrbanToronto) Close to five months since UrbanToronto first broke the story of the extraordinary Mirvish+Gehry development plan for Toronto's Entertainment District, a second public consultation regarding the proposal was held on the evening of Tuesday February 19th at Metro Hall. Hosted by Ward 20 Councillor Adam Vaughan, on hand to give details and answer questions were Craig Webb, representing architect Gehry Partners, Peter Kofman representing developer Projectcore, and owner of the site and driving force behind it, theatre impresario and art collector David Mirvish.

Prior to the presentation, the public had an opportunity to view schematic floor plans, sections, elevations, and a scale model of the proposal within the context of the neighbourhood. Where the first consultation in December introduced the proposal to the public and recorded the resultant concerns of those in attendance, in this meeting Craig Webb opened with a far more detailed account of the plans for the development as they currently stand. He was accompanied by members of the technical team from Gehry Partners and developer Projectcore.

Webb began by expressing the firm's excitement to be working in Toronto again, four years after the completion of the addition to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Webb reminded the audience of Gehry's subsequently reawakened connection to his hometown and his continued desire to create projects of significance to the city. To provide a glimpse of the working process, Webb showed Gehry's first loose sketch of his vision revealing three towers as very sculptural forms rising from a combined base.

Later in the presentation Webb flashed the image below of a recent model, as he did at the OCAD University announcement the previous week for the Princess of Wales Centre for Visual Arts, and stated "this is where Frank really wants to take the project", no doubt a confounding moment for those straining to understand how the expressive quality captured will translate to a finished building design. The idea is to create podiums with a unified design from which three towers emerge as if from clouds, each with a unique architectural identity.

Webb explained that at the AGO it was important to Gehry to relate that building to the smaller scale of the nearby residential houses, thus that design was scaled horizontally. In contrast, the firm is taking a different approach at this location, sited as it is amongst larger buildings. The team has been looking at how to integrate the scale of the historic city with what's coming in the future, a dilemma that any city builder wrestles with. Toronto has a lot of very tall buildings that are sprouting up right now, but according to Webb, the "interrelation with the street facade is really the key to this project." When studying the existing streetscape, the team identified two key readings: 1) the historic buildings of 4 to 5 storeys establish a lower datum line; while 2) the adjacent Lightbox and similarly tall buildings of 6 to 8 storeys establish a second datum line. The podium height of the new project takes its cue from that second level.

Gehry's office has had what Webb characterizes as vigorous conversations with City Planning about what the King Street 'wall' or 'edge' should be, and about how it should engage the sidewalk. Both sides are working to establish what the goals are for that frontage, in terms of accessibility, openness, and sidewalk width. A partial section through the site (image below) illustrates how the building meets the ground and gives one a sense of the generous sidewalk space that Gehry is trying to achieve. "We really think that the sidewalks need to be widened from what's currently 3-3.5 metres up to 6 metres in some areas so we intend to push the building façades back." The section exceeds City standards in terms of providing an adequate pedestrian zone, a planting zone, as well as additional area which is intended to be used as public gathering space, including restaurant spill-out.

It's this all-important podium that, as Webb describes, "creates edges of the public realm, which creates the cityscape, and which in turn creates neighbourhoods". The strategy that Gehry is taking is to "create a very landscaped and terraced podium to this building. It starts at the street edge and—moving up the building—at the level of the first datum, the building begins to step back, terracing the façade and creating outdoor spaces. We're trying to create a multi-level environment with a lot of public use. The ground level is mainly retail and restaurant spaces, and those public spaces will step up across the terraces, bringing people higher up into the building. Instead of being a single layer of public uses, we're expanding it vertically."

"We intend to undulate the building façade back and forth so that it's not just a straight, street wall, but it has some relief to it and has pockets where restaurants are expected." The images below are of gestural models used by the firm as a starting point to understand the architectural flow and movement of the building. "The intention is to create a lot of transparency, colour, graphic, and excitement."

When it was first revealed in the fall, the model above ellicited some groans from those who misunderstood its intent and were not able to see beyond what they perceived as "toilet paper" adorning it. In the model below a potential treatment of the podium is more developed. Webb expects many more models will be created before a final plan is formulated.

Webb emphasized that although the models do not represent a finished design, the interior designs are further along than a massing study. They have been worked out very carefully in terms of structure, elevator core servicing, and even preliminary suite layouts.

Webb walked the audience through the floor plans, beginning with the ground level plan, pictured below. "Our intent is to activate all four sides of the site." Instead of merely relying on bustling King Street, the team feels there are advantages to putting retail frontages on the more intimate side streets as well.

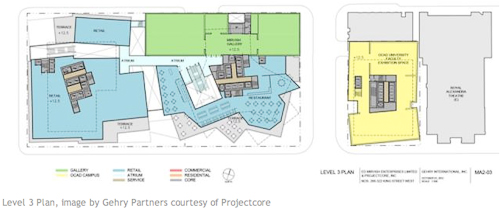

Below, retail space is indicated in blue, while the residential lobby components, whose 'front door address' Gehry feels is more appropriately suited to the smaller streets, is orange. Loading and parking access is shown in brown, while commercial office entry areas appear in red. OCAD U's entrance, shown in yellow, is on Duncan Street, the school's main south campus artery, while direct street access to the Mirvish Collection is indicated in green from Pearl Street.

The podium itself is 6 storeys in height and retail and restaurant spaces wrap the lower 3 floors. Creating a diagonal connection through the project site between King and John streets is a public arcade access that will climb from street level via stairways and escalators, and culminate on the 3rd floor. The street level lobbies to the upper level retail areas are indicated in light blue in the image above.

Level 2 is programmed with more retail and an atrium space that connects to the floor below. In addition, a restaurant with terrace is envisioned on the NW corner, overlooking what the City is planning as the 'John Street Cultural Corridor.'

Active public uses and landscaped south-facing terraces continue on the 3rd floor, with the first section of the extensive, 3-storey Mirvish art collection, also beginning here. OCAD U’s expanded facilities, organized on two floors in the Phase 1/easterly tower, include a faculty exhibition space here on level 3, and the art instruction and studio space on level 4.

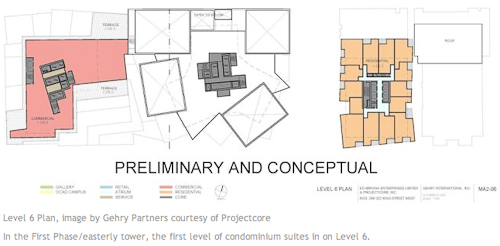

Some commercial office space is planned for the podiums on levels 4, 5, and 6, and it can be seen in red above and below. The Mirvish Collection galleries continue on these levels as well.

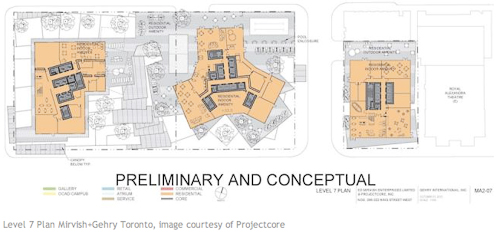

A residential terrace, with outdoor amenity and garden space of varying sizes and orientations, are provided on top of both podiums at the 7th level. Residential indoor amenities, which can open to the exterior, are also situated here. Condominium units rise on the floors above, with the towers at 82, 84, and 86 storeys. The unit count is approximately 2700, but that will likely change as the layouts are developed, and around 300 parking spaces are currently proposed.