Three of the world’s leading practitioners of public-interest architecture addressed “The Importance of Being a Socially Sustainable Architect” at IIDEX Canada. Liz Ogbu, Michael Murphy and Janna Levitt related their experiences in the non-profit and private sectors through case studies of compelling work.

Three of the world’s leading practitioners of public-interest architecture addressed “The Importance of Being a Socially Sustainable Architect” at IIDEX Canada. Liz Ogbu, Michael Murphy and Janna Levitt related their experiences in the non-profit and private sectors through case studies of compelling work.

1) A former innovator at IDEO.org and Design Director at Public Architecture, Liz Ogbu opened by re-stating the UN’s original definition of sustainability: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” drawing attention to social consciousness rather ‘green building’, a term more commonly used nowadays.

Public Architecture engages firms and non-profit organizations in the design of sustainable, public-oriented projects that enhance interactions and communication. Investigating the great potential of waste, it developed “Design for Reuse Primer”* a resource listing projects that incorporate used materials into the language of the building. It demonstrates how to make projects viable to the community by describing the processes and lessons learned in each case study: how materials were worked into the design, how funding was achieved. By telling their story, and “linking fact and emotion” (what it was before, what it could be in the future), it speaks to something greater.

And not only full-fledged buildings have design impact. IDEO.org’s project in Kenya is a small-scale business: a kiosk selling water and products. SmartLife seeks to eradicate poverty by means of public interest design initiatives that integrate building with medical, nutritional and hygienic considerations.

Because of their capacity to reflect on both the big and small scale, “architects have the ability to be systems thinkers, not merely designers of buildings,” says Ogbu. It is a multi-dimensional role: Architect as instigator, facilitator, collaborator, translator, advocate, and designer.

2) Michael Murphy is a founding partner of Boston’s MASS Design Group, a not-for-profit firm that best represents the role of designers in public health. Through the development of hospitals in Rwanda and Haiti, MASS has acquired lessons that may also prove to be particularly relevant to USA and Canada, where the largest growing industry is healthcare infrastructure.

These lessons highlight the importance of: 1) Patient Centricity; 2) Natural ventilation; 3) Transparent systems; 4) Programs for long-term wellness, not reimbursables; 5) Controlling infection to save lives (and avoid litigation!); and 6) Civic infrastructure.

In the USA, healthcare buildings suffer from a plethora of problems, including labyrinthine plans, a lack of natural light, and a prevalence of airborne diseases. Murphy encourages North America to “look beyond its borders and not only produce different business models but rethink the facility into a community model.” A simple strategy, like revisiting the typical layout of a ward in the Butaro hospital in Rwanda, led to an increased connection to the outdoors. By implementing forward-thinking approaches, facilities’ design can be beautiful and dignified, more humane and less reminiscent of a “conveyor belt.”

3) Janna Levitt is a Principal of Toronto-based Levitt Goodman Architects, a firm that espouses the learning through making practice by in-house building and doing experimentation alongside. “As architects, every opportunity is an opportunity to innovate,” says Levitt, also an active lecturer, critic, and community activist. The social sustainability aspect of their projects looks at maximum use/re-use, cultural opportunities, and the need to be open to innovation.

The adaptive reuse design of the Native child and Family Services building called for a green roof that could be used by urban First Nations people for counseling, playing, and ceremonial purposes but, when running short on monies, was put in jeopardy. Levitt Goodman worked with the client to secure funds to get it built, not typically in an architect’s scope.

The conversion of a medical building into single room occupancy at Leonard Avenue required a clever consideration of pre-manufactured trailers and shipping containers and a balancing of logistical and procedural elements. In addition to responding to the program and meeting the client’s mandate that no tenant need move out during the renovation, the architects went the extra mile to propose cost-effective rooftop housing as “garden apartments in the sky,” envisioning a way to greatly enhance the residents’ quality of life.

The above-mentioned ideologically-driven architects are each a force to be reckoned with in their own right, although common to all three is their ability to identify design problems and come up with design solutions. As proponents of socially sustainable architecture, they highlight the importance of understanding the needs and desires of the ultimate end users, not just the paying clients, and emphasize the value of working collectively in order to arrive at innovation.

*Public Architecture’s “Design for Reuse Primer” is now available for download. http://www.publicarchitecture.org/reuse/ Images courtesy of firms.

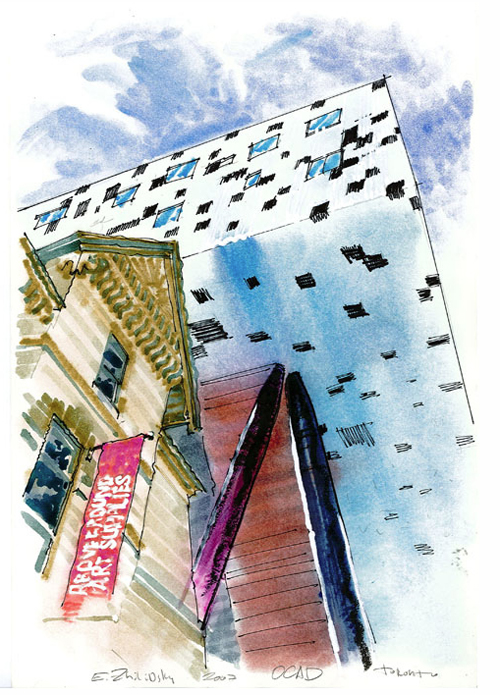

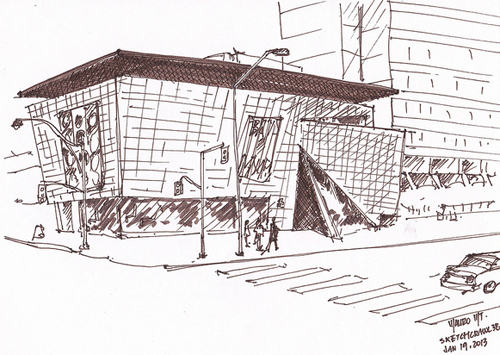

With the bleak weather lately, I’ve needed all the inspiration I can find. Lo and behold, I discovered it in the visual dispatches of Urban Sketchers (USK), a blog site showcasing sketches of artist correspondents around the world.

With the bleak weather lately, I’ve needed all the inspiration I can find. Lo and behold, I discovered it in the visual dispatches of Urban Sketchers (USK), a blog site showcasing sketches of artist correspondents around the world.