Public conversations about city building are taking place in Canada’s largest urban centre. Most recently, one panel, engaging parents, child educators, heath professionals and big city-thinkers, aims to create a healthier, more walkable Toronto for children.

Public conversations about city building are taking place in Canada’s largest urban centre. Most recently, one panel, engaging parents, child educators, heath professionals and big city-thinkers, aims to create a healthier, more walkable Toronto for children.

University of Toronto’s Faculty of Kinesiology & Physical Education hosted “What Happened to Walking?” – Encouraging active school travel in Toronto. Professors on the panel shared their research findings from the ongoing BEAT project (Built Environment and Active Transport), which studies the topic from multiple perspectives: physical and mental health; financial costs; urban landscapes; and, the child’s point of view (including fears, obstacles). While within certain distances walking is still the most common mode, it has been on the decline and children are heavier and weaker than ever.

The evening’s keynote speaker Jennifer Keesmaat emphasized the importance of this simple and meaningful childhood experience rooted in nostalgia. Who doesn’t have stories about walking to/from school, or about exploring one’s surroundings while dillydallying on the way home? The symposium was one of the first opportunities to hear from the newly-appointed chief planner for the City of Toronto.

Keesmaat, an approachable young urbanist (and mother), claims that by having vastly separated our uses (read: sprawl) and privileging moving vehicles, “children have been designed out of public space.” Predominantly driving environments, with their countless turning lanes and blank façades, are unworthy of children’s curiosity. They are isolated, unsafe, and unfriendly for anyone, much less kids! Walking is more imperative than ever and our immediate surroundings need to be more conducive to travel on foot.

In light of the city’s unprecedented growth (Toronto is the condo epicentre) and staggering infrastructure deficits, are we, maybe, at the cusp of a change? A new theory entitled ‘Peak-Car’* suggests that in various cities of the world we are witnessing an aggregate levelling off in average car mileage perhaps the result of car saturation and changing mobility patterns: fewer people owning cars, walking more.

And while the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is investing significantly in regional transportation, Keesmaat stresses the need to “create places where we see walking as a fundamental part of our transportation planning.” We can support a walking culture by giving pedestrians priority, not only by providing safer circulation but also by thinking about “how we embody a space and a place”. There is strong local support for developing denser, sustainable, walkable neighbourhoods near shops and services, and a desire to move away from car-centric environments.

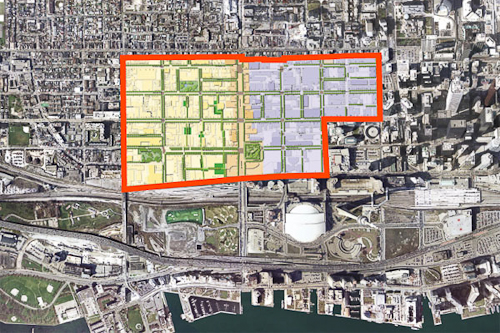

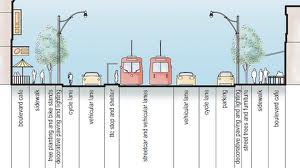

The City has identified key avenues (above) to cultivate as "walking habitats" – attractive, all-season pathways characterized by wide sidewalks and buffers, greenery, and buildings that don’t overwhelm the street and that allow sunlight to hit the pedestrian realm. Creating environments where everyone can share in a high quality of life, and building neighbourhoods and walking habitats that are supported by great public transit and cycling networks is really, as Keesmaat says, “an equality and justice issue.” And while infrastructure presents its challenges, she iterates that the way to ultimately increase healthy modes of commuting begins, you guessed it, with parents.

Moderating the panel discussion, Christopher Hume, an outspoken architecture critic and urban issues columnist of the Toronto Star, remarked on the irony that “we have to argue for walking”, and the fact that “we have to devise policies” to make this most basic of human functions possible.

Although the focus of the talk was on how to promote greater independent mobility among children, it shifted to the functioning of the built environment as a whole and the larger issue of how citizens relate to the city. Hume criticizes the motorized-mindset and states that the ambivalence we’ve shown is a “reflection of how we feel about the environment in which we live. We cannot afford convenience any longer.” If we truly believe that cities should be designed for people, it will require making cultural choices and hard sacrifices in order to reclaim the streetscape and re-design it to be shared amongst people and cars.

Never has the job of planners been more important. If in fact true, the underlying principles of ‘Peak-Car’ give practitioners “much more freedom to think about what kind of cities they want.”* They curate a set of design guidelines and best practices that can be integrated into policy in order to encourage more healthy use of public spaces like streets and sidewalks. Toronto has plenty of precedents to learn from...

To see this public speakers’ series lecture, click here. *Toronto Chief Planner Jennifer Keesmaat made reference to a London Times article on ‘Peak-Car theory’. See her official blog at http://ownyourcity.ca/